(The Unfortunate Consequences of Long-Term Care Insurance Partnership Plans)

By John H. Robinson, Financial Planner (March 2024)

“The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the Government and I’m here to help.’” This memorable one-liner from the late President Ronald Reagan was directed toward the federal government. However, an examination of individual states’ “Long-Term Care Insurance Partnership Programs” finds that state governments are every bit as adept/inept as the federal government at implementing well-intentioned policies that inflict financial harm on their residents. In this essay, I will explain how certain states’ efforts to encourage consumers to purchase long term care insurance policies to help them preserve and protect their retirement savings and to help the states reduce their Medicaid expenditures may be having exactly the opposite effect.

Medicaid Expenses and State Budgets

Medicaid is the joint federal-state program that is administered at the state level to provide safety net assistance to people with limited income and assets. Custodial care ,including nursing home care, is among the largest components of Medicaid spending, and it is a component that has continued to grow as the Baby Boomer generation ages.

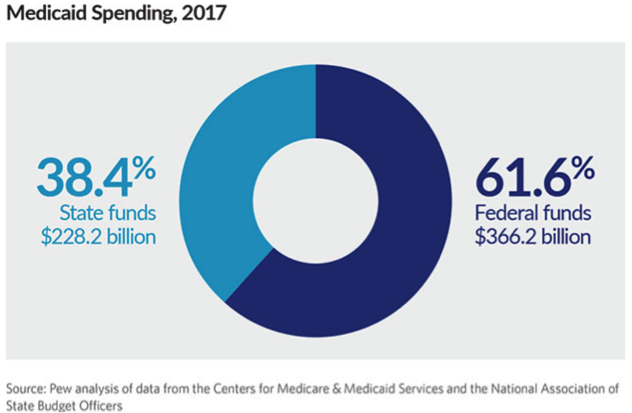

According to a 2020 Pew Research study, the 50 states collectively spend 17% of their revenue on Medicaid. As per the study, “Medicaid’s claim on each revenue dollar affects the share of state resources available for other priorities, such as education, transportation, and public safety.” As of 2020, six states spent more than 20% of their revenue on Medicaid: New York (28.7%), Rhode Island (23.4%), Pennsylvania (22.2%), Missouri (22.1%), Louisiana (22%), and Massachusetts (22%). These expenditures are after the reimbursement the states receive from the federal government, which in 2017 covered between 50% and 74.6% of the individual state’s Medicaid bills.

The Best Laid Plans

It is no secret that long-term custodial care expenses represent one of the biggest threats to the financial security of retirees. According to a 2023 Cost of Care Survey conducted by LTC insurance provider Genworth Life, the median cost of nursing home care in the U.S. is $8,669 per month for a shared room and $9,733 for a private room. The cost is considerably higher in some states and round-the-clock home care can be even more costly than care in an assisted living or nursing home facility.

To qualify for Medicaid assistance in paying for these expenses, consumers must demonstrate need by first spending down their assets and using their available income to pay for custodial care expenses out of pocket. The strict Medicaid qualification rules have compelled many consumers to preserve assets for themselves and their heirs by transferring assets out of their names many years in advance of their potential custodial needs. Such efforts, while legal, only compound the states’ Medicaid woes.

Other consumers sought to address the threat to their future financial independence and security by purchasing long term care insurance. Long term care insurance existed as a niche product in the 1980s, but evolved rapidly into a mainstream risk management tool in the 1990s as insurance companies saw the aging Baby Boomers as a huge potential market for this type of coverage.

In the early 1990s, a few progressive states – New York, California, Connecticut, and Indiana – came to view long term care insurance as a potential tool for reducing its Medicaid expenditures. The mechanism for creating the incentive for consumers to purchase long term care insurance came in the form of a promise from the states to disregard a certain amount of assets from the Medicaid qualification equation. In theory, this protection would compel fewer consumers to transfer assets out of their estates and the benefit pools that policyholders accrued in their long-term care policies would reduce the need for Medicaid assistance.

To ensure the effectiveness of the plan, these four states partnered with insurance carriers to create “Partnership Program” policies that required consumers to purchase policies with certain minimum benefit features that typically included a minimum daily/monthly benefit amount, a minimum benefit period, a minimum eligibility period, and a minimum inflation adjustment to the daily/monthly benefit.

The asset disregard formula adopted by California and Connecticut was a simple dollar-for-dollar match with the benefits paid under a long-term care insurance policy under the Medicaid asset qualification requirements. For example, if a consumer received $150,000 in long-term care benefits before applying for Medicaid, they could retain an additional $150,000 of assets beyond the usual meager maximum amount of retained assets permitted to qualify for Medicaid assistance. New York took an even more progressive and aggressive approach to incentivizing its citizenry to purchase partnership policies by promising the exclusion of all assets to policyholders. Indiana applied a hybrid model that allows purchasers to obtain dollar-for-dollar protection up to a certain benefit level as defined by the state and offered total asset protection on all policies purchased with benefits above that minimum threshold policy structure.

The passage of the federal Deficit Reduction Act in 2006 made it easier for other states beyond the original pioneering four to establish their own Partnership Programs. Although they vary from state to state, most states that moved forward in creating an LTC Partnership program adopted the same type of asset disregard formula as California and Connecticut.

What Could Go Wrong When States Promote Insurance Sales?…EVERYTHING!

By 2014, 41 states had established long-term care insurance partnership programs. 2006 to 2014 also marked the period during which the insurance companies that had so eagerly leaped into the long-term care insurance space came to realize that their zeal to compete for Baby Boomers’ premium dollars had caused them to badly underprice their policies. With this realization came waves of premium increases to existing policy holders. Ironically, just as many new states were jumping on the Partnership Program bandwagon to promote Partnership plans to their residents, existing policyholders were beginning to feel the sting of double digit premium increases. As it turned out, the widespread adoption of Partnership Programs provided one last sales boost to a product that was already in rapid decline. Met Life, the third largest player in the long-term care insurance market, stopped issuing new contracts in 2010. The second largest seller, John Hancock, exited the market in 2016. Genworth, the largest player (by far) in the LTC market space, discontinued sales of new long-term care policies in 2019. (Source: Top 10 LTC Companies)

For many policyholders, the decision to purchase Partnership Plans has been a financial disaster. Unlike traditional long term care insurance policies, which permit policy holders to downgrade their policy benefits in order to lower premium costs and maintain coverage, Partnership Plan policies require consumers to maintain certain specified minimum benefits regardless of the policyholders’ ability to pay the premiums. Unfortunately, what the states did not do (but definitely should have) was require the insurance companies whose products they were endorsing and promoting to keep their premiums fixed.

The following two real-life examples illustrate the folly of the Partnership Plan concept. Both of these policies were issued by Genworth in New York.

Example 1. Policy issued 10/5/2006.

Policyholder age at issuance = 58. Current age = 75

| Policy Features | Original Policy Structure | Current Policy Structure |

| Elimination Period | 90 days of covered care | 90 days of covered care |

| Max. Daily Benefit | $190.00 | $388.15 |

| Daily Benefit Inflation Adjustment | 3.5% Compound | 3.5% Compound |

| Benefit Period | 3 years | 3 years |

| Lifetime Benefit Pool | $208,050.00 | $425,024.25 |

| Annual Premium | $896.4 | $5,472.55 |

Example 2. Policy issued 11/19/2011.

Policyholder age at issuance = 59. Current age = 72

| Policy Features | Original Policy Structure | Current Policy Structure |

| Elimination Period | 30 days of covered care | 30 days of covered care |

| Max. Daily Benefit | $250 | $538.74 |

| Daily Benefit Inflation Adjustment | 5% Compound | 5% Compound |

| Benefit Period | 3 years | 3 years |

| Lifetime Benefit Pool | $273,750 | $589,920.30 |

| Annual Premium | $2,752.35 | $10,673.88 |

The highlighted figures illustrate the magnitude of the premium increases the policyholders have endured. Further, both policyholders received letters from Genworth relating to the Haney v. Genworth Class Action settlement in which Genworth was required to disclose its intention to seek approval from the NY State Insurance Commission to increase premiums by an additional 143% over the expected life of the policy class.

The first example represents a contract that was purchased with the minimum required features under the partnership plan. As such, the features of this policy cannot be modified. In the second example, there is some room to reduce premium by modifying the policy features to the minimum level, but the modest reduction in premium is not sufficient to make the premium manageable if the premium increases, as Genworth plans to seek. In both cases, the policyholders have elected to terminate their current coverage in return for a paid-up policy equal to 150% of the premiums they have paid. This nominal paid-up coverage is likely far less than the policyholders would have if they had elected to self-insure and invested the premium money instead.

As illustrated, both policyholders had accumulated benefit pools that would have likely kept them off New York’s Medicaid roll in the event they should require long term custodial care. Instead, by failing to curtail the insurance companies’ right to increase premium on policies issued under the Partnership Program, New York has effectively increased the likelihood that these policyholders will end up receiving Medicaid benefits. As a result of the stupendous premium increases, policyholders now have less retirement savings available to pay for long term care policies and are being forced to drop their policies just as they approach the age when they are likely to need the coverage.

It is important to note that some states have attempted to address this problem by amending their rules to allow Partnership Plan policyholders to modify their policy structures to help avoid or ameliorate the impact of premium increases. Connecticut, for example, allows policyholders to reduce some benefit features below the initial minimum standards at the time of issuance if the policyholder has experienced a 50% or greater increase in premiums. Other states (e.g. Virginia) have modified their rules to permit policyholders who have attained a certain age or have paid premiums for a defined period of time to modify their policies to help keep their polices in force while maintaining the policy’s standing in the Partnership Program. However, two states with the largest numbers of Partnership policies issued – New York and California – have failed to adopt meaningful amendments that would enable beleaguered long-time policyholders to keep their Partnership policies in force.

Summary

In conclusion, the failure of the states to anticipate that legions of long-term care insurance policy holders would be forced to drop their partnership policies in the face of massive premium increases is inexcusable. Premium increases among the major carriers began in earnest in the late 1990s (source: Long Term Care Insurance Rate Increase History) with first-class action lawsuits over the issue making headlines as early as 2002. Based upon my ongoing anecdotal experience, the Partnership Programs in New York and California, in particular, are doing immeasurable harm to residents who bought into their Partnership Program sales pitches and paid premiums for the past 10–20+ years. Premium increases of 400% or more have adversely impacted these policyholders’ standard of living in retirement, and the termination of their Partnership Program policies as the premiums become unmanageable increases the likelihood that these people will end up on states’ Medicaid rolls. This is exactly the opposite of the stated goal of the partnership plans. President Reagan’s famous quip could not be more applicable.

John H. Robinson is the owner/founder of Financial Planning Hawaii and Fee-Only Planning Hawaii. He is also a co-founder of fintech software maker Nest Egg Guru.

Sources:

Overview of the Long-Term Care Partnership Program (9/9/2005) Government Accountability Office

American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance

Nursing Home Costs and Payment Options

Pew Research Study on State Medicaid Spending (2020)

New York Partnership for Long Term Care

Long Term Care Insurance Rate History

Genworth Cost of Care Survey(2023)

Connecticut Office of Policy and Management

Related Articles by This Author:

3 Villains, No Heroes – The Genworth Long-Term Care Insurance Saga

Should You Accept a Genworth Long-Term Care Insurance Settlement Offer?

What if the Company that Issued my Long-Term Care Policy Fails?